8 Things to Know About Lav Diaz’s “Ang Panahon ng Halimaw”

Jun 7, 2018 • Macky Macarayan

Jun 7, 2018 • Macky Macarayan

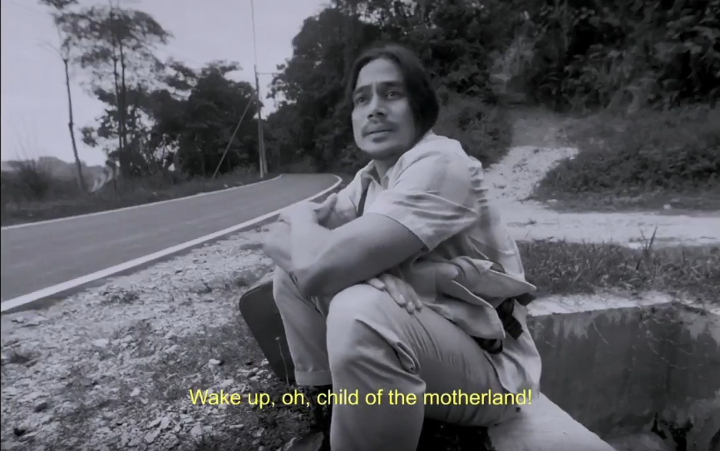

Lav Diaz is one filmmaker that continues to push the boundaries of cinema, with his penchant for black-and-white, long takes and running times that will likely rearrange the molecules in one’s brain (Meryl Streep, 2016). Starting with 2013’s Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan, Diaz’s films got to be screened outside of arthouse venues and film schools, bringing forth his visions of society into a wider audience. His new film, Ang Panahon ng Halimaw, again criticizes a society besieged by unspeakable evil, one that is neither ethereal nor imaginary.

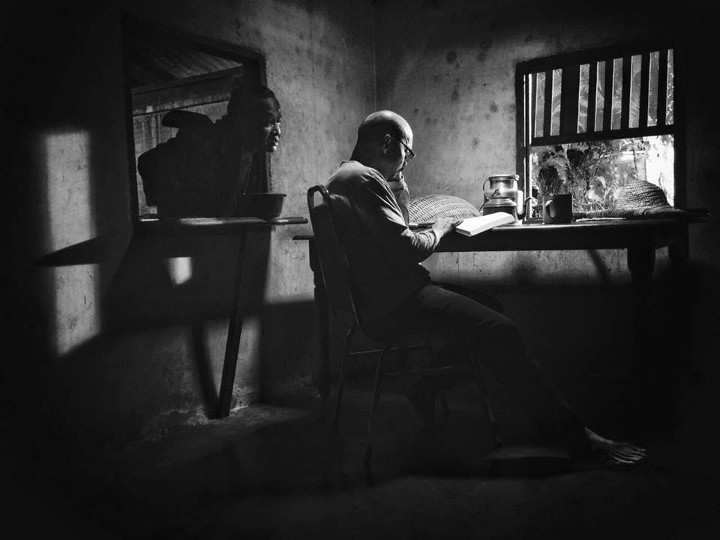

Although the film can be considered a musical, Diaz presents all songs in acapella, perhaps a haunting lamentation to the Philippines’ endless misfortunes. Every character sings their motivations and aspirations, and through Larry Manda’s use of chiaroscuro and long takes, the experience, although not consistently electrifying, is assuredly provocative.

Although the film is set in 1979 during Ferdinand Marcos’ violent Martial Law regime, the events and characters depicted are today’s horrors, from the extrajudicial killings to the spread of fake news, up to the elimination of enlightened individuals who are deemed a threat to the fascist rule of a few.

In the film, Piolo Pascual plays Hugo Haniway, a poet, and writer who embarks on a search for his disappeared wife Lorena (Shaina Magdayao). During the earlier part of the film, Hugo reads some of his writings amongst the townsfolk and talks about the current affairs of their community. Later, he conveys his hesitation about Lorena’s departure in a letter, despite acknowledgment of Lorena’s duty to provide medical care to their fellowmen. In most parts of the film, the paramilitary forces try to strike down any source of enlightenment, which is viewed as an uprising against their power.

As if to say that we have not learned from the horrors of the past, Diaz, who wrote all the songs in the film, uses lines that are repeated several times (e.g. “Ako ang hari, ako ang pari… ako ang yayari…”). Repetition is one of the prominent devices that Diaz employs to illustrate the cyclical nature of violence and oppression, and our seeming indifference to it all. The town plagued by the devil is even aptly named “Ginto,” which when taken literally, translates to “gold.” Guns, goons and gold— the oppressors in this film have them all.

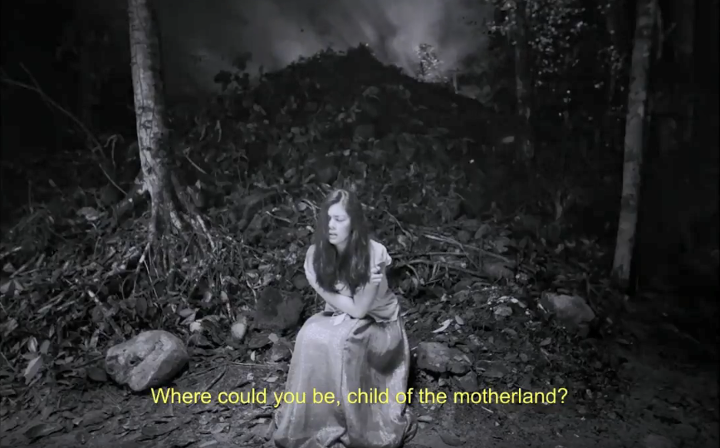

Two of the most prominent characters in the film, Lorena (Magdayao) and Kwago (Pinky Amador) have the noblest of intentions, yet they are continually cast aside by the paramilitary forces. Lorena only wants to provide medical aid to the distressed residents of Ginto, while Kwago is seeking justice for her murdered husband and son. Their situation strikingly reflects the current political climate in the Philippines, where powerful women are being silenced. To add another layer of criticism, Tinyete (Hazel Orencio), being in a state of power, uses her position to destroy subversion. And it isn’t just turning a blind eye that is Tinyete’s greatest sin; it is actually her active participation in the rape, kidnapping and murder of women and children that is most grotesque.

Land, or soil is perhaps the most common element in all of Lav Diaz’s films, probably because it is his point of revolution, his struggle (according to a colleague). Hence, we see characters and their relationship to the land they are situated in. For example, we see Aling Sinta digging for root crops, almost in futility; then, the story takes place in a remote barrio, where paved roads which symbolize progress are almost nonexistent. Take these into present context, what with the Spratlys dispute and our mounting debt to China, and the parallelisms might as well be subtitled onscreen.

Noel Sto. Domingo plays the demagogue Chairman Narciso, who literally has another human face at the back of his head, akin to Voldemort attached to the back of Professor Quirrell’s head in “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.” Sound familiar? Here’s another unsubtle characteristic: Chairman Narciso’s dialogue is incomprehensible, but his blind followers seem to understand what he is saying.

Diaz has grown weary of metaphors, having used them since the 90s to depict the country’s sordid state. Although the film still has them, the references are notably more overt, screaming to be recognized. Perhaps, this is where Diaz is now, asking the audience what more can he do to rally the people into action.

* All screenshots taken from the movie’s trailer below:

Input your search keywords and press Enter.