Filipino Words 101: 8 Ways You’re Doing It Wrong

Feb 11, 2015 • Christa I. De La Cruz

Feb 11, 2015 • Christa I. De La Cruz

Who can blame us? More people know English and if we want to be the global citizen that we want to be, we must learn the language. At least, that’s what we thought.

Before we completely lose our national pride by switching to foreign grounds, it’s time to go back to our roots and relearn our national tongue. Listed here are 8 mix-ups most of us are guilty of when we speak/write (mostly write) in our first language:

Example: “Uy, kumusta ka naman? Ang taba mo na! Tagal na natin di nagkikita a!”

A root word (which, in this case, is “pinto”) with the suffix “-an” indicates the space where the word happens or is placed. For example, “kainan” means a place where you eat (kain), “babuyan” means a place where pigs (baboy) are kept, and, “pintuan” means the frame where the door (pinto) is placed.

Example: “Huwag po nating sandalan ang pinto. Ang di makakasakay next train na lang. Pakiusap po, huwag po tayong magtulakan!”

Example: “Guwapo naman sila pero mas yummy sina Marco at Luigi.” #ChoosyKaPa

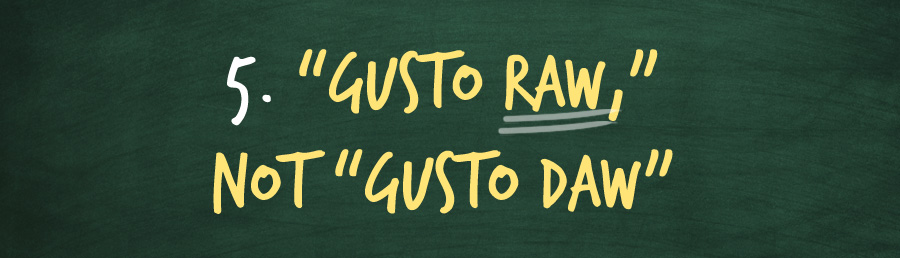

If the word before “daw” ends in a vowel or W/Y, then use “raw.” For everything else, it stays as “daw.” The same is true for “din/rin” and “dito/rito.” An exception to this is when it’ll sound weird, of course. For example, if the prior word ends in “-ri,” the tongue doesn’t roll right if you still use “rin.”

Example: “Crush ka rin daw ng crush mo! Bet mo ba raw magkita bukas?!”

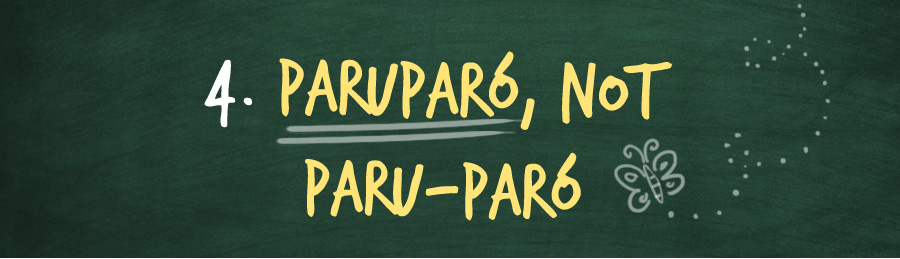

Unless your dictionary says that “paro,” “gamo,” and “kili” exist, you should write “paruparó,” “gamugamó,” and “kilikili.” Another commonly misspelled word with this rule is “ala-ala” instead of “alaala.” Because what exactly is “ala”?

Example: “Paruparóng bukid, bukid paruparó…?!” #FolkSongFail

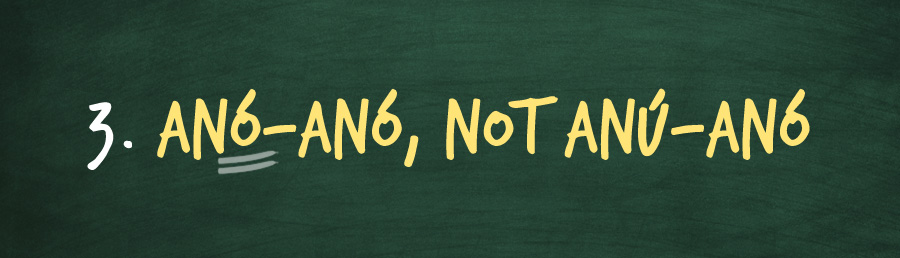

And, unlike “alaala” and “paruparó,” the former three words have their own meanings – thus, “anó-anó,” “taon-taon,” and “patong-patong”

Example: “Kung anó-anó pang sinasabi mo diyan, ang sabihin mo na lang, di mo na ako mahal!” #HugotPaMore

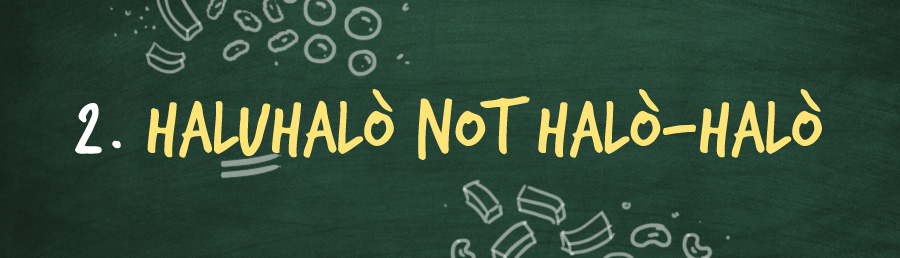

Some repeated words become a whole new word–unlike “anó-anó,” which is basically a lot of “anó” or an enumeration of “anó.” When a new word is formed, the rule is to remove the hyphen and change the O to U.

Haluhalò, the dessert, is a new word even if it is a derivative of “halò” because of the way you serve the ingredients: mixed or “nahalò.” Halò-halò is an entirely different word.

Example: “Halò-halò ang mga sangkap sa haluhalò.” #WhatIsConfusing

“Nang” has five basic uses: (1) as synonymous to “noong”; (2) as synonymous to “upang” or “para”; (3) as a combination of “na” and “ng”; (4) as a connector for repeating verbs; and (5) as an adverb. For everything else, use “ng.”

Example (according to use):

(1) “Nang umalis ka, hindi na ako umasa pa.” #HugotPaMore

(2) “Kailangan ko na magpa-makeover nang maka-move on na!” #HugotPaMore

(3) “Sobra nang pagkakamartir ang ginagawa mo, teh! Di ka naman si Jose Rizal!” #HugotPaMore

(4) “Paganda ka nang paganda, feeling mo naman papansin ka niya.” #HugotPaMore

(5) “Wag kang kumain ng nakahubad” (Don’t eat someone naked) is a world of a difference from “Wag kang kumain nang nakahubad” (Don’t eat while naked). Know what I mean? #IKnowWhatYoureThinking

These, of course, won’t automatically make you the best Filipino speaker there is. But it’s a start. After all, you are a Filipino and this will always be your own.

(Reference: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino: Manwal sa Masinop na Pagsulat)

Input your search keywords and press Enter.