8 Ways That Leonard Nimoy Was a Model Human Being

Mar 5, 2015 • Paolo Jose Cruz

Mar 5, 2015 • Paolo Jose Cruz

[dropcap letter=”W”]hen eulogizing his former Star Trek cast member Leonard Nimoy, George Takei referred to him as “the most human person I’ve ever met”. That means a lot coming from a Japanese-American actor who spent the tumultuous 1960s downplaying his gay identity. In his own subtle way, Leonard Nimoy was one of geek culture’s most prominent Social Justice Warriors. And he lived that ideal long before the term was coined (sarcastically) by dismissive fanboys trying to preserve the nerd canon status quo, and diluted by earnest but misguided slacktivists on Tumblr.

Nimoy’s most famous characters live on, of course – cross-species stoic Mr. Spock and omnicidial Decepticon tyrant Galvatron have already been sufficiently recast in the public imagination. But there’s no replacing the main himself.

Let’s remember the gestures that helped make the universe a more just and understanding place.

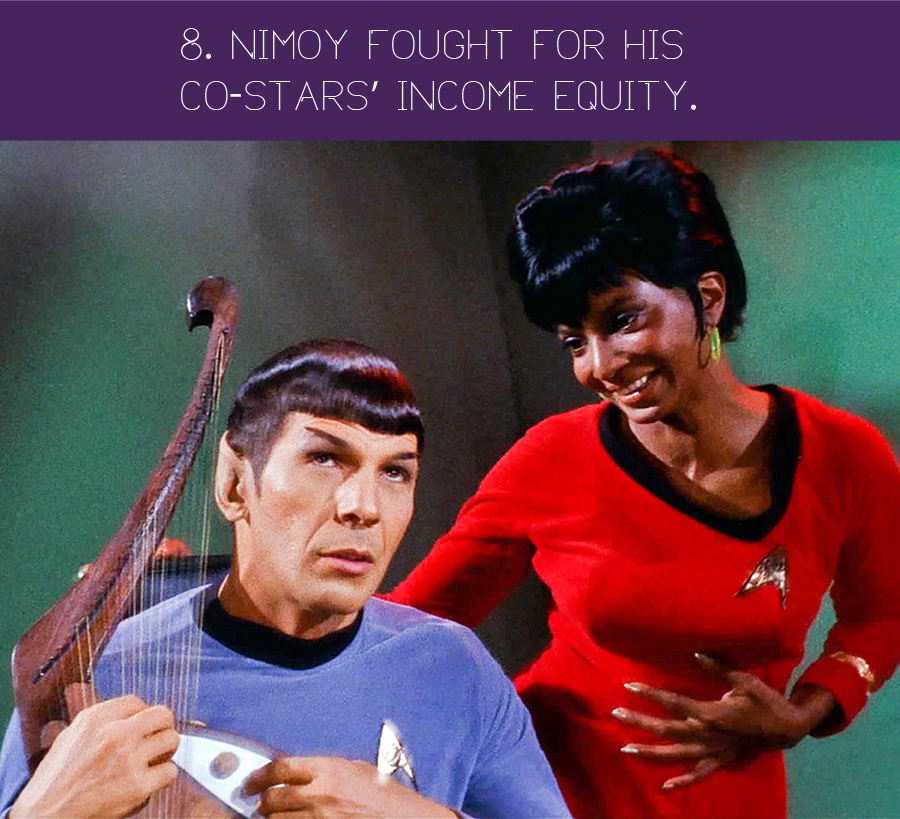

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry called Nimoy “the conscience of Star Trek” for good reason. His co-star Walter Koenig recalled how Nimoy kicked up a stink in the Desilu Productions front office, when he learned that black actress Nichelle Nichols was not earning as much as himself and Koenig, for her role as Communications Officer Uhura in the first Star Trek series.

Note that this situation predates the large-scale discussion of the “glass ceiling” faced by women and minorities in the American workplace – there was no talk of “leaning in” aboard the starship Enterprise. But Nimoy seemed determined to live out the the show’s seemingly utopian ideals of economic justice and social equity.

This wasn’t the last time that Nimoy fought for pay equity for his fictional crew-mates. When he found out there was supposedly not enough budget to have Takei and Nichols reprise their characters for Star Trek: The Animated Series, Nimoy threatened to walk out of the production unless they were brought in.

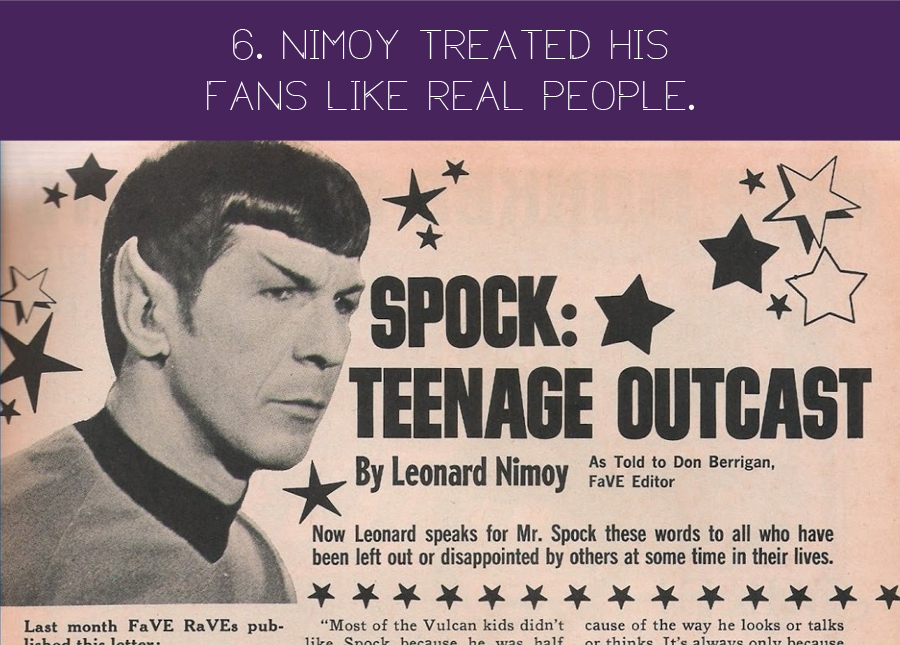

Nimoy may not have been a biracial person himself – but he played an allegorical one on TV! And for an actor dedicated to his craft, portraying the half-Vulcan, half-human Spock gave him a valuable emotional (if not social) insight to being a person whose identity, allegiances, and loyalties were divided across species (and by extension, cultural) lines. So when an ethnically mixed girl named F.C. reached out to him via a letter to a teen magazine, he chose to write her a mature, nuanced response in the next issue.

The full exchange is linked here, and it’s worth reading as a fine example of a celebrity interacting with a high school age fan, and recognizing her as a flesh-and-blood person, first and foremost.

Nimoy seemed to be the prime example of a socially engaged, non-Zionist Jewish-American in showbiz. While he never campaigned around the issue of peace in the Middle East, he was an outspoken supporter of a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict, and he was fine with the idea of a divided Jerusalem.

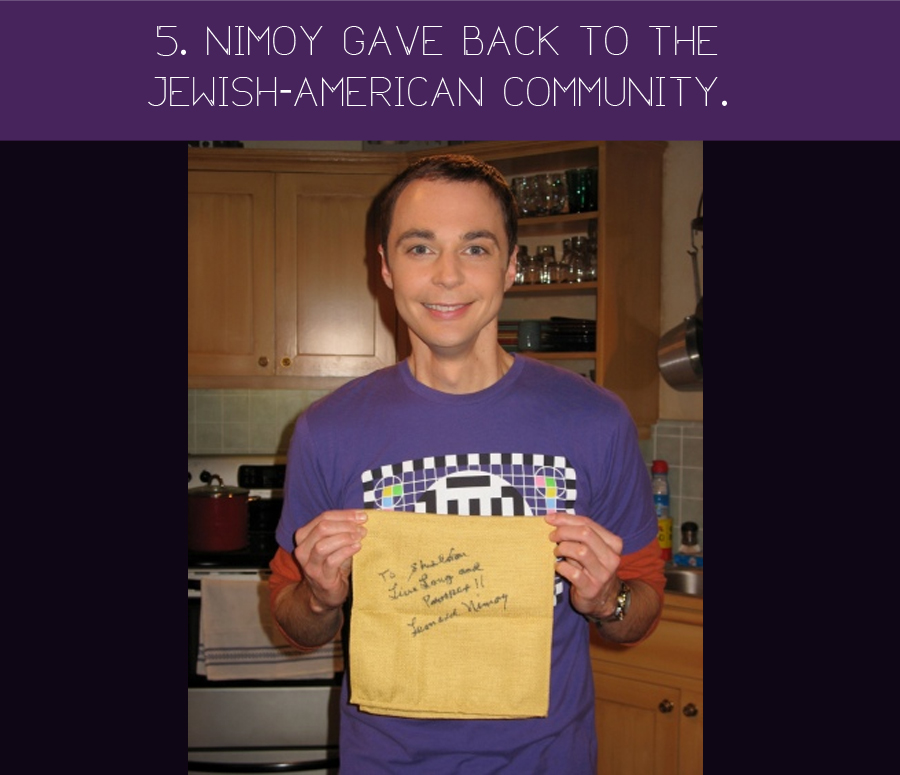

However, perhaps Nimoy’s most interesting act of Jew-centric philanthropy – at least to latter-day geeks – is connected to his (non-)appearance on faux intellectual sit-com The Big Bang Theory. Nimoy himself declined to guest on the show, but he agreed to sign a cocktail napkin that lead character Sheldon Cooper eventually gets a hold of, in the episode “The Bath Item Gift Hypothesis”. Nimoy eventually recovered the prop, and auctioned it off in support of Beit T’Shuvah a non-profit Jewish community center in Los Angeles, as part of their “Steps to Recovery” gala, which supports treatment programs for recovering substance abuse addicts.

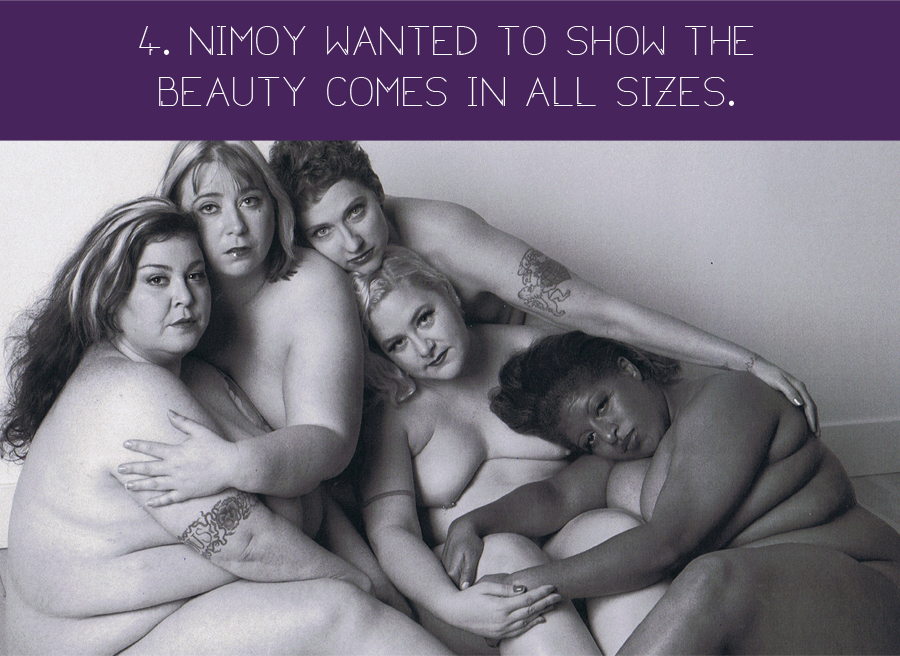

Aside from his work in front of the camera, Nimoy was also a dedicated studio and portrait photographer. Perhaps his most famous work was a collection titled The Full Body Project, which aimed to recreate famous iconic images of female sexuality, using models whose sizes ranged from the statistical median – the kind of women who could be image models for manipulative Dove ad campaigns – to full-figured, Tess Holiday-esque plus-sized models.

It’s kind of ridiculous that we live in a universe where cleft-browed Klingon women can be treated as representations of exotic, unconventional beauty, and yet Nimoy’s project would be greeted with such blatant hostility.

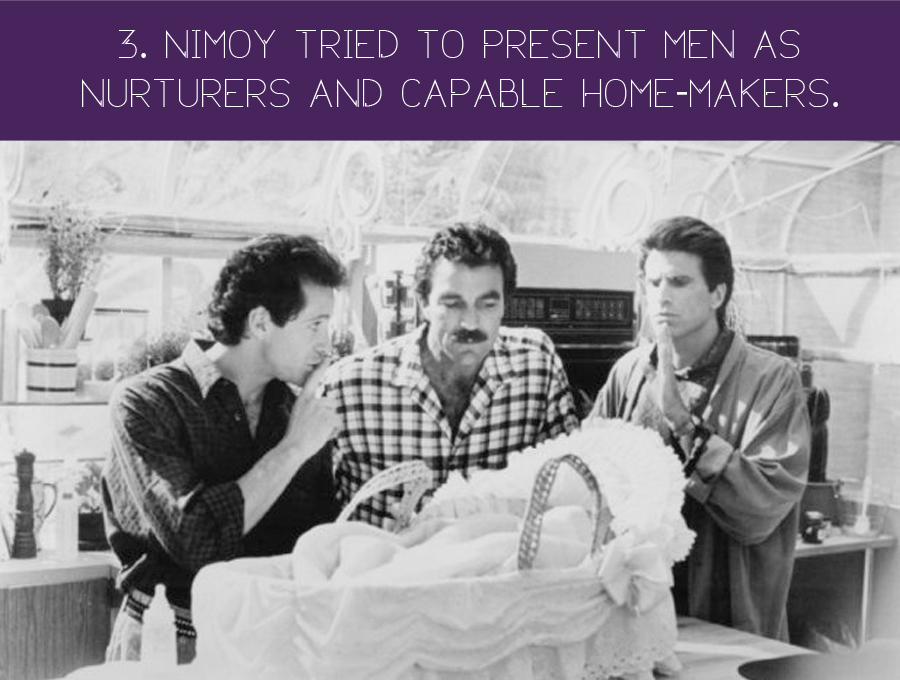

Nimoy directed Three Men and a Baby, a late ‘80s comedy of errors about three very different bachelors who suddenly find themselves with joint responsibility over an infant left on their doorstep. As with any cultural product, the jury is forever open about whether the movie falls short of its goals – critics of the film say that it downplays the role of motherhood, for one thing. But Nimoy has gone on record claiming that he wanted to use standard Hollywood fare as a means to reconsider gender norms, in the context of the American “Greed Decade”.

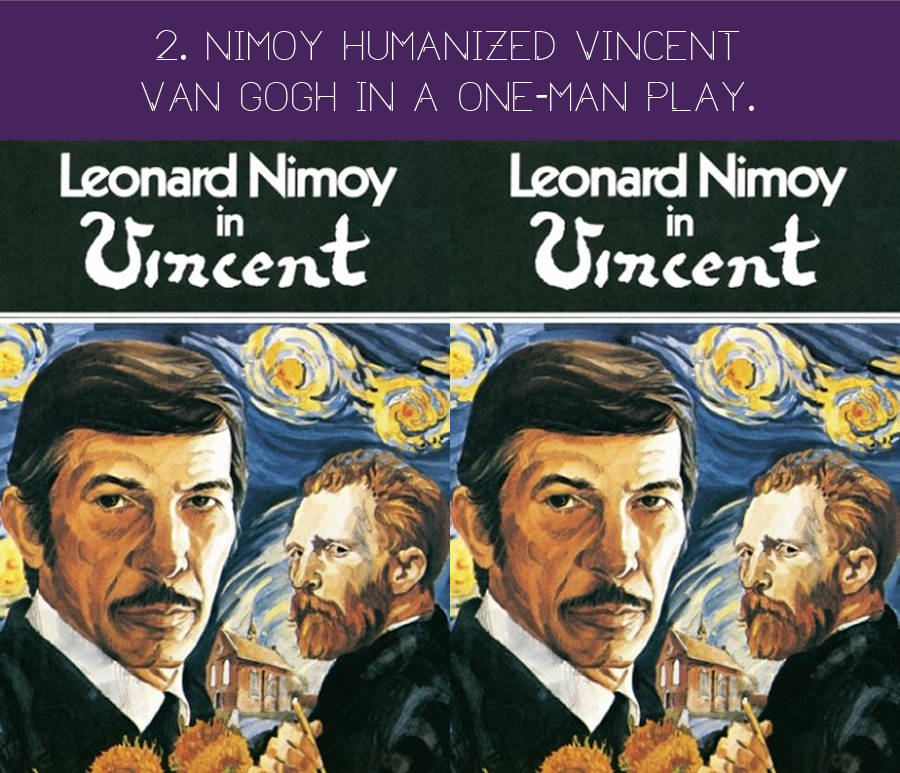

Nimoy wrote and acted in Vincent, a one-man dramatization of the letters exchanged between artist Vincent Van Gogh and his brother Theo. In the process, he depicted a more touching, nuanced portrayal of Vincent than his usual reputation as “that crazy-ass tortured artist who cut off his ear and died broke”. It’s all too easy to write off the intersections of art creation, mental health, and singular genius as trite, cliché award-bait. But while such lazy stereotypes live on, then shows like Vincent are worth restaging.

The music video for “The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins”, from the album Two Sides of Leonard Nimoy, looks “highly illogical” now, with its campy mix of folk guitar, dancing hippies, and Tolkien lore fan wank. But in July of 1967, when the performers’ elongated ears stood in for both Hobbit and Vulcan lineage, it must have seemed like a genuine expression of solidarity between two niche genres, which had yet to become part of the mainstream cultural DNA.

Input your search keywords and press Enter.