We Filipinos have long prided ourselves on being a resilient bunch. And we’re not just tough, we’re happy, sometimes even placing in the top 5 of global happiness surveys. We’re the folks who laugh in the face of terrible situations, smiling while wading through waist-deep waters, cracking jokes when the news cycle gets dark.

But this pandemic hits a little different. COVID-19 has upended our lives in ways we’ve never experienced before. We’re now isolated from our communities, many of us unable to go to work and do the things that used to give us joy. As we helplessly watch the number of deaths and confirmed cases climb, some of us are struggling to cope.

Many of us know that clinical depression is a disease that is largely affected by genetics, but our environments also play a crucial role in our mental health. And these are unprecedented, anxious times we live in.

We’re a nation known for our bright disposition, yet we’ve been reported to have the highest number of citizens suffering from depressive disorders in Southeast Asia: about 3.3 million. Out of every 100,000 people, 2.5 males and 1.7 females have attempted suicide. (But according to the World Health Organization, the actual numbers could be much higher. Because of the stigma surrounding mental health, these suicide incidents are likely underreported.)

To the Philippines’ credit, we’ve come a long way in terms of mental health awareness. Two years ago, the Mental Health Act (RA 11036) was passed to provide a comprehensive framework for mental healthcare in the Philippines. But because the implementation of the bill is only in its early stages, we aren’t seeing much of its effects during this crisis.

“It’s only been two years,” says Dr. Ronald del Castillo, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of the Philippines Manila’s College of Public Health. “Not only that, the implementing rules and regulations were only passed a year and a half ago. So that’s not really enough time really to see how it’s rolled out.”

In a recent study from the Zheijiang University School of Medicine in Hangzhou, China, researchers found that women, nurses, and healthcare workers were at a greater risk of worsening mental health conditions during this pandemic. This should come as no surprise — not only are they working longer, more grueling hours, they also have to contend with the threat of becoming infected; in the Philippines, one out of 10 people with COVID-19 are doctors.

“It took a toll on everyone emotionally, especially at the onset, because we were all trying to beat the clock and work as quickly as we can to figure out the disease,” says Angeli Jane Blanco, RITM’s Communications and Engagement Chief. “We knew this day would come — that we’d barely come home to our families, eat dinner with them, watch TV with them. But this is our work and this is what we are called to do.”

Blanco says that there are no formal mental health programs in RITM. “We are all extremely focused on fulfilling our mandate,” she says. “It has been a running joke around the Institute, though, that COVID-19 response is a very long team-building activity.”

Del Castillo acknowledges that the government is (rightly) more concerned with curbing the spread of the virus itself, but thinks that this scarcity of mental health resources points to a larger problem. “I think the fact that mental health and wellbeing is not well integrated into our approach is a reflection of our broader culture wherein we don't prioritize mental health and wellbeing,” he says.

Blanco says that there are no formal mental health programs in RITM. “We are all extremely focused on fulfilling our mandate,” she says. “It has been a running joke around the Institute, though, that COVID-19 response is a very long team-building activity.”

Del Castillo acknowledges that the government is (rightly) more concerned with curbing the spread of the virus itself, but thinks that this scarcity of mental health resources points to a larger problem. “I think the fact that mental health and wellbeing is not well integrated into our approach is a reflection of our broader culture wherein we don’t prioritize mental health and wellbeing,” he says.

Even though fighting the virus itself should be our main concern, we can’t afford to neglect our mental wellbeing. Now that this crisis has caused us to lose the normal structures of our lives, feelings of depression and anxiety are now becoming more commonplace. While some may find comfort in the communal nature of this grieving, many more of us are still struggling to deal with the loss, this new normal, and the emotions that come with them.

We are grieving in many ways. Some of us have lost loved ones. Others are grieving over canceled plans. Many are grieving over the loss of livelihood and stability.

What many of us are feeling now is what psychologists call “anticipatory grief”. Normally, this term is used to describe the grief we experience before a death. This could be triggered by a diagnosis or even a passing thought that we’ll lose a loved one eventually. But this kind of grief doesn’t have to center on death.

In an article for the Harvard Business Review, death and grieving expert David Kessler explains: “Anticipatory grief is also more broadly imagined futures. There is a storm coming. There’s something bad out there. With a virus, this kind of grief is so confusing for people… We’re feeling that loss of safety. I don’t think we’ve collectively lost our sense of general safety like this. Individually or as smaller groups, people have felt this. But all together, this is new. We are grieving on a micro and a macro level.”

Though an unpleasant feeling, the stress response isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

It helps us adapt to the disruptions in our lives, and can motivate us to accomplish tasks and reach our goals. Stress also produces the fight-or-flight response, causing the body to release chemicals like cortisol, which elevates your senses — the better to avoid potential danger, such as jumping away from an oncoming vehicle.

While stress can be helpful in some contexts, a constant state of stress weakens the immune system. The stress response elevates blood pressure and heart rate, inhibits digestion, and increases blood cholesterol levels. It can also indirectly harm our bodies through unhealthy coping strategies, such as smoking, drinking, and eating unhealthy foods. Ironically, stressing over staying healthy could be the worst thing you can do for our health.

Even before the government first announced that it would be implementing community quarantines, supermarket and pharmacy shelves were emptied of rubbing alcohol and cleaning supplies. The DTI has had to step in and set limits on the purchase of basic goods to prevent panic buying and hoarding. These are symptoms of stress.

When we’re stressed and deep in a mindset of self-preservation, letting our fear and anxiety get the better of us, there is a real danger of losing empathy and succumbing to selfishness. We then become prone to tribalism and all the toxic behaviors that come with that, such as racism and hoarding. This then feeds into a cycle of negativity, which eventually eats away at our mental health.

And now that we’re physically isolated from each other for a prolonged period, holding on to that sense of community becomes an even bigger challenge. This is why the act of bayanihan is so important; as we take care of each other, we remind ourselves that we’re part of something bigger, that we’re not the only ones feeling this pain.

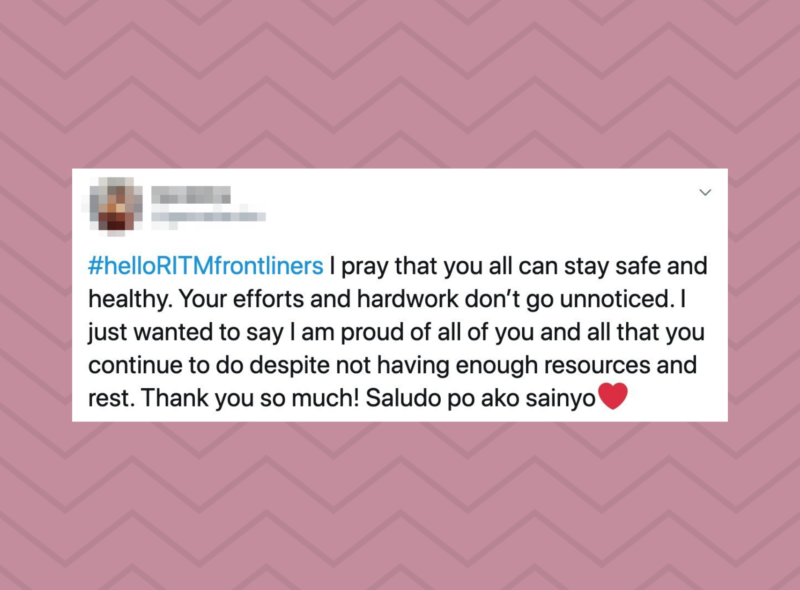

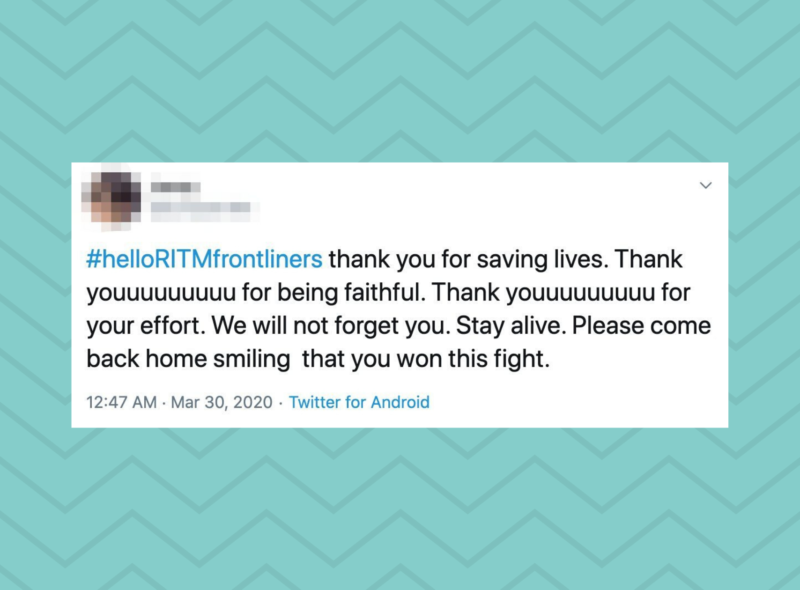

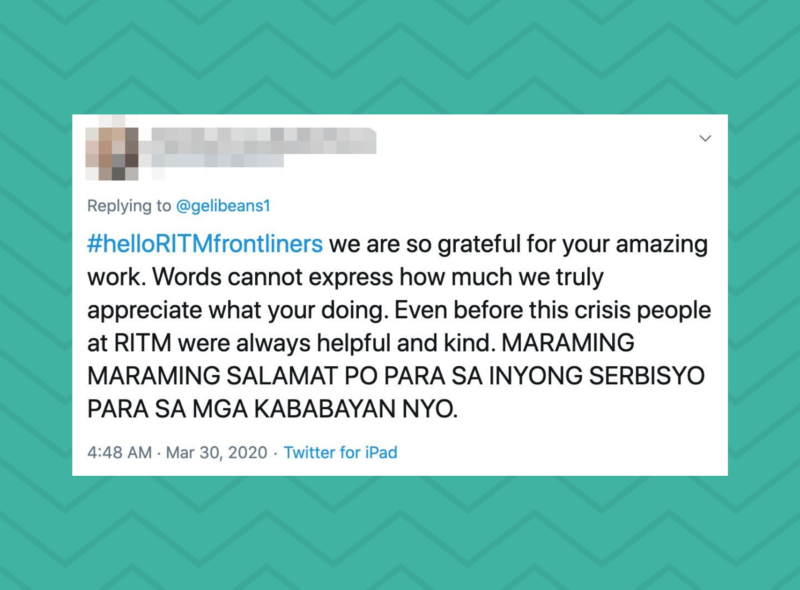

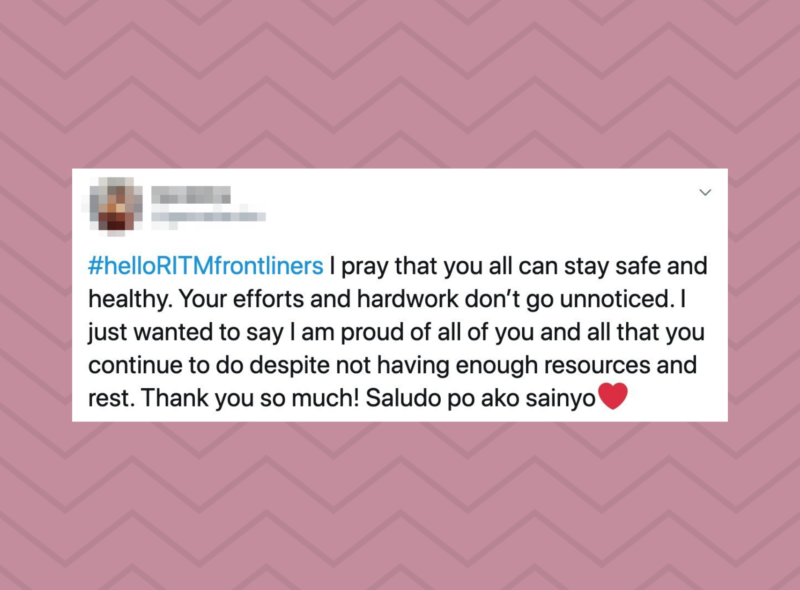

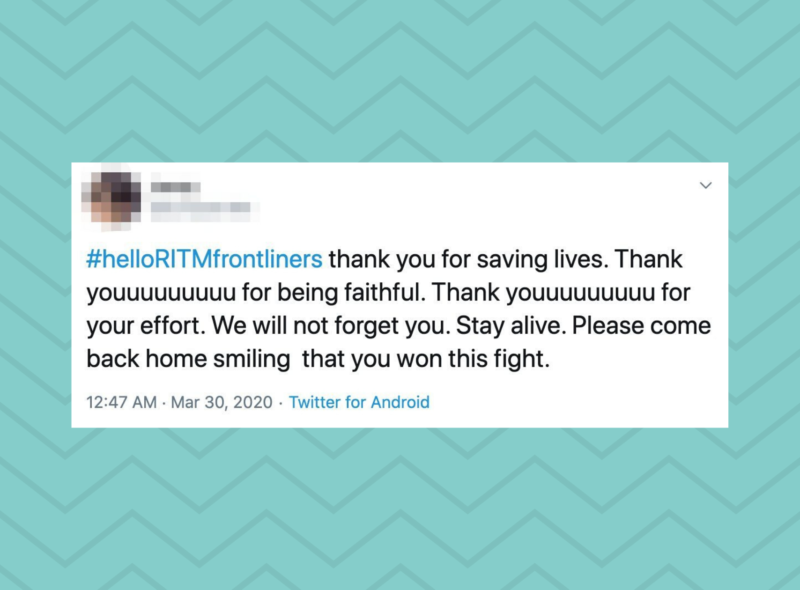

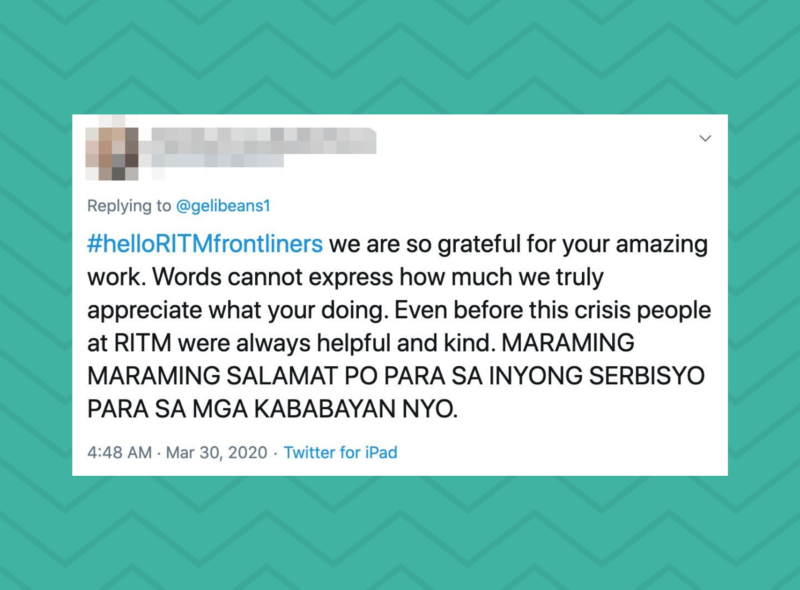

Blanco started the hashtag #helloRITMfrontliners to boost the morale of their staff. It took only a few hours for it to trend on Twitter.

“The messages sent through #helloRITMfrontliners were all heartfelt and touching,” she says “If only the public can see how, in the middle of everything we do, we’d stop a little to check and smile at our mobile phones! We have been reenergized, to say the least. Seeing how much the public recognizes us and our efforts is a great reminder for all of us why we do the things we do.”

Blanco started the hashtag #helloRITMfrontliners to boost the morale of their staff. It took only a few hours for it to trend on Twitter.

“The messages sent through #helloRITMfrontliners were all heartfelt and touching,” she says “If only the public can see how, in the middle of everything we do, we’d stop a little to check and smile at our mobile phones! We have been reenergized, to say the least. Seeing how much the public recognizes us and our efforts is a great reminder for all of us why we do the things we do.”

This pandemic will end soon. None of us know how or when, but it will end. But even after the COVID-19 threat recedes, our mental health issues that have resulted from the pandemic — or have been aggravated by it — will remain.

Some of us will have a hard time readjusting to life on the other side. Apart from health workers, people who already have a history of mental illness may be more at risk. Not only are they more likely to suffer from other illnesses, those who are depressed may have a more difficult time looking for work or pursuing goals after all this is over. And while most of us are raring to see our loved ones IRL, those who are depressed could have a more difficult time reconnecting with their social circles.

This health crisis highlights the need for a more robust mental health policy.

But there are some things we can do individually to minimize the effects of stress on our wellbeing.

None of us is experiencing this crisis in exactly the same way, and how we cope will greatly depend on our unique situations. The first step is understanding our emotional state and recognizing the symptoms of stress.

Understanding our emotional state is the first step to managing it effectively. Dr. Del Castillo recommends doing these 5 things:

“I try to wake up at the same time I normally would, and I go to bed as I normally would. I eat whenever I would normally would. Routine is very stabilizing. It can create a good foundation, especially at a time when things seem so unpredictable.”

2. Limit watching the news and social media.

“I know it’s tempting to watch the news, but actually avoid the news. I really only watch the news a couple of times during the day. That’s a trigger. It’s stressful. I try to avoid social media as much as I can. I know we get a lot of our information on social media, which is fine. But remember, a lot of the information we get on social media will have been filtered in one way or another before it gets to us. So you know, is it factual? Is it helpful? Is it reliable, I’m not so sure especially at a time of anxiety. So I really only follow the DOH and the WHO in terms of getting my facts, but otherwise, I avoid exposure to social media. And when I do look at social media, I try to look at more helpful things, like videos of cats and dogs and animals.”

3. Exercise.

4. Connect with people.

“Social distancing does not mean emotional distancing. So you need to be in touch with people, especially if you don’t really live with anyone else. Or if you’re far from loved ones, it’s good to stay in regular contact with friends with loved ones.”

5. Give.

“Volunteering can be very helpful in promoting our mental health and wellbeing. Do something nice for your neighbor. Maybe you have an elderly or neighbor that you can run an errand for and you can get creative. There are ways to keep your physical distance while still helping each other. Acts of kindness is a way also to alleviate some of our stress around this time.”

Stress is an unavoidable part of life. But when the effects of stress and anxiety are debilitating and you are unable to function, ask for help. Here are some helplines you could reach out to: https://8list.ph/mental-health-crisis-line-philippines